the art and science of critical thinking

Critical thinking is, really, thinking on purpose.

Or perhaps thinking with purpose.

It's thinking about the way we think, to make sure we're not thinking nonsense.

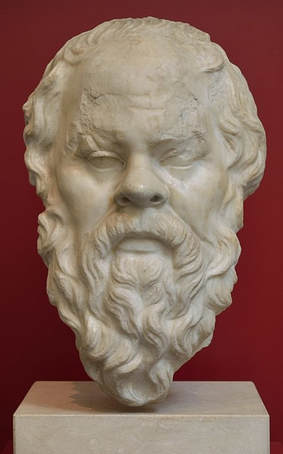

Seems like a pretty sensible idea. Socrates invented it, around 400 BC. Ish.

Wiki has a useful summary:

Plato wrote that Socrates established the fact that one cannot depend upon

those in "authority" to have sound knowledge and insight.

(I disagree with his massive emphasis on rational thought, but on this, I'm a huge fan of this bloke already. Ed).

He demonstrated that persons may have power and high position and

yet be deeply confused and irrational.

(Yerdon'tsay. Ed )

He established the importance of asking deep questions that probe profoundly into thinking before we accept ideas as worthy of belief. ( I can so go with this. Although we don't get all our "knowledge" from "thinking". Just saying. Ed)

He also established the importance of seeking evidence, closely examining reasoning and assumptions, analyzing basic concepts, and tracing out implications not only of what is said but of what is done as well. His method of questioning is now known as "Socratic Questioning" and is the best known critical thinking teaching strategy.

He:

- highlighted the need for thinking for clarity and logical consistency.

- asked people questions to reveal their irrational thinking or lack of reliable knowledge.

- demonstrated that having authority does not ensure accurate knowledge.

- established the method of questioning beliefs, closely inspecting assumptions and relying on evidence and sound rationale.

Plato recorded Socrates' teachings and carried on the tradition of critical thinking. Aristotle and subsequent Greek skeptics refined Socrates' teachings, using systematic thinking and asking questions to ascertain the true nature of reality beyond the way things appear from a glance.

Socrates set the agenda for the tradition of critical thinking, namely, to reflectively question common beliefs and explanations, carefully distinguishing beliefs that are reasonable and logical from those that — however appealing to our native egocentrism, however much they serve our vested interests, however comfortable or comforting they may be—lack adequate evidence or rational foundation to warrant belief.

Socrates had some good points. Athough, clearly, we should question our own belief in him, too ... always deploy critical thinking. And we need to acknowledge that Socrates (and Plato) took out at the knees that sophisticated systems and complex theory thinking at the heart of pre-socratic thinking, and informed the wholly inadequate entire modernist, mechanistic, reductionist endeavour which claimed - and still does - that the universe is just like a big ole machine, was simple and linear and not complex and emergent, and can be predicted down to the last detail.

Yeah, right. That thinking worked out well, then. The splendid Boulton, Allen and Bowman in "Embracing Complexity" talk of how "Western pre-Socratic philosophers and the Eastern philosophical traditions—in moving away from a reliance on explaining nature in terms of the whims of various gods—did indeed focus on flow, interdependency, and the emergence of structures and patterns. They developed worldviews that are almost identical to complexity. They saw regularities and patterns emerging in an immanent way, that is to say, from within, not imposed from the outside. And they did not see such regularities as permanent, perfect, or fixed."

So we love the socratic questioning of the belief in the bosses knowing what they're talking about. But that also refers to Socrates and Plato, too. According to complex theory, as it emerged before them, or after as part of post-modernist thinking, maybe none of us do ... maybe the best bit of critical thinking is acknowledging that We Just Don't Know As Much As We Think (and Probably Won't Ever).